By: Shafi Karimi

June 27, 2025

Mehrmah, a 23-year-old transgender Afghan woman, stands quietly in the halls of the Louvre Museum in Paris. For many, it is a place of art and beauty; for her, it represents survival. Just a few years ago, she was running for her life first from her family in Kunduz, then from violence in Kabul, later from sexual assault in Pakistan, and finally from the existential threat posed by the Taliban. Today, she lives in France, where she experiences relative safety but not without pain.

Born in Kunduz province in northern Afghanistan, Mehrmah was assigned male at birth and named Sayed Ashraf by her family. As a child, she did not have the language to describe who she was, but from an early age, she understood that her mannerisms, speech, and sense of self did not align with the gender imposed on her. “I didn’t know what ‘transgender’ meant,” she recalls. “I only knew that I wasn’t a boy.”

Family Violence and Forced Silence in Afghanistan

When Mehrmah reached puberty around the age of 13 or 14 her family’s reaction was swift and brutal. Her hair was forcibly shaved. She was beaten repeatedly. She was removed from school and confined to her home, effectively imprisoned for her identity.

“They locked me inside like I had committed a crime,” she says. “My brothers, cousins, and relatives insulted me every day. They used slurs I didn’t even understand at the time.”

Such experiences are not uncommon for LGBTQ+ individuals in Afghanistan. According to multiple human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, family violence is often the first and most severe form of persecution faced by queer Afghans. Many are beaten, forcibly married, subjected to “conversion” attempts, or expelled from their homes.

Unable to endure the abuse, Mehrmah fled Kunduz for Kabul as a teenager, hoping the capital would offer anonymity and freedom.

Life as a Transgender Woman During the Republic Era

Before the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, Afghanistan’s Republic period offered limited and fragile space for LGBTQ+ individuals particularly in urban areas like Kabul. Same-sex relations were technically criminalized under the Penal Code, but enforcement was inconsistent, and some LGBTQ+ people managed to survive quietly, especially within informal networks.

“There was no protection, but there was some room to breathe,” Mehrmah explains.

Still, life was harsh. Due to her feminine appearance, employers refused to hire her. Like many trans women in Kabul, she was pushed into survival economies, including dancing at private gatherings. During this period, she reports being raped multiple times by civilians and members of the police, kidnapped, forced to drink alcohol, and subjected to torture.

According to advocacy groups, transgender women in Afghanistan were particularly vulnerable even before the Taliban takeover, facing sexual violence with near-total impunity. Police abuse was frequently reported, and victims had no realistic access to justice.

Photo: (Courtesy of the new york times)

Taliban Rule: Existence Criminalized

The fall of Kabul marked a turning point from marginalization to outright annihilation.

Under Taliban rule, LGBTQ+ identities are considered crimes punishable under their interpretation of Islamic law. While the Taliban do not publish formal statutes on LGBTQ+ issues, testimonies and documentation show a pattern of arbitrary arrests, beatings, torture, sexual violence, and killings.

“Had the Taliban identified me, I would not be alive today,” Mehrmah says.

Human rights organizations estimate that dozens of LGBTQ+ individuals have been arrested or tortured since 2021, though the real number is likely far higher due to fear and underreporting. For queer Afghans today, the choice is stark: flee the country or face imprisonment, violence, or death.

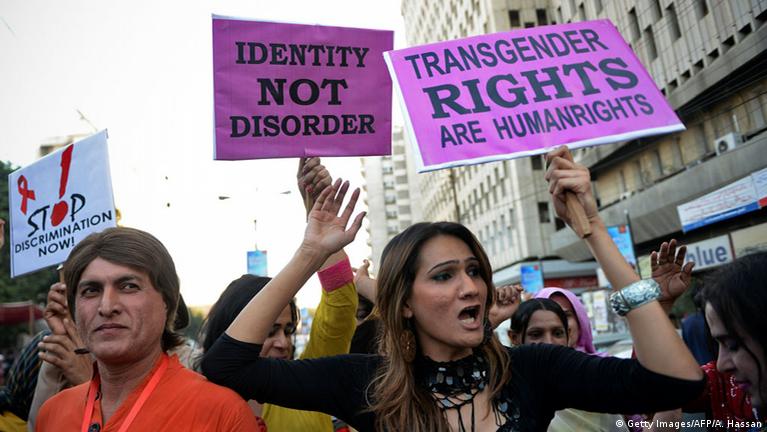

Flight to Pakistan: Another Layer of Abuse

When Mehrmah fled Afghanistan, she sought refuge in Pakistan like hundreds of thousands of other Afghans. Instead of safety, she encountered renewed violence.

In Pakistan, she says she was gang-raped by ten men, assaulted repeatedly, and tortured. Pakistan criminalizes same-sex relations under colonial-era laws, and transgender people despite some legal recognition face widespread violence.

According to Pakistani human rights groups, transgender individuals are frequently subjected to sexual assault, extortion, and police abuse, with very low rates of prosecution. Afghan trans refugees face even greater risks due to their undocumented status.

While Pakistan has legal recognition for transgender people, activists report that transgender individuals face some of the highest rates of sexual violence and murder in the country. Afghan trans refugees are even more vulnerable due to language barriers, poverty, and lack of legal status.

“Pakistan broke me in ways Afghanistan didn’t,” Mehrmah says.

Mehrmah survived through the support of informal LGBTQ+ networks and eventually connected with an international organization that assisted Afghan queer refugees. Through these channels, she was introduced to the French embassy.

After one and a half years of waiting in Pakistan, she finally received a visa and left for France.

Photo: Getty Images/AFP/A. Hassan

Life in France: Safety with Scars

France offered something she had never known: legal recognition.

In Paris, Mehrmah can live openly as a transgender woman. She can access healthcare, learn the language, and seek asylum. Hate crimes based on gender identity are punishable under French law, and discrimination can lead to prison sentences.

But safety does not erase trauma or hardship.

Mehrmah struggles financially, navigating an unfamiliar system while coping with PTSD. She lives in shared housing and has faced harassment in public spaces, particularly at night. “Freedom doesn’t mean life is easy,” she says. “It just means I’m not hunted.”

She is learning French, but the language barrier isolates her. Employment remains difficult. “I want to work,” she says. “I want dignity not pity.”

Perhaps the most painful challenge in Paris comes from fellow Afghans.

Mehrmah says she is often mocked, stared at, or verbally abused by members of the Afghan community. “They use the same words they used back home,” she says. “The same hate, just in a different country.”

Some avoid her entirely. Others accuse her of bringing “shame.” She says this rejection deeply affects her mental health. “I escaped the Taliban,” she says, “but I didn’t escape their mindset.”

Activists confirm that LGBTQ+ Afghans in Europe frequently face hostility from their own diaspora, including people who publicly advocate for democracy and human rights.

A Life Still Under Construction

Despite everything, Mehrmah refuses to disappear.

She attends French language classes, dreams of stable work, and hopes one day to study. She wants a future where survival does not depend on hiding or performing for others.

“I didn’t choose this life,” she says. “But I choose to live.”

She pauses, then adds: “Please don’t recognize the Taliban. For people like me, recognition means erasure.”

Mehrmah’s story reflects the reality of hundreds of Afghan LGBTQ+ individuals many still trapped in Afghanistan, others stuck in transit countries, and some rebuilding fragile lives in Europe.

Under Taliban rule, queer Afghans face arrest, torture, sexual violence, and execution. Under the Republic, they lived without protection. In exile, they are often invisible.

Yet they continue to survive.

(Photo: Courtesy of Mehrmah)

A Community Erased from Global Conversations

Nemat Sadat, an Afghan LGBTQ+ rights activist and director of the Roshanaya Network, confirms that Mehrmah’s experience reflects a broader pattern.

“Family rejection is almost universal among LGBTQ+ Afghans,” Sadat explains. “And even in Europe, many Afghans who claim to support democracy and human rights still hold Taliban-like views on queer people.”

Sadat notes that not a single major international conference on Afghanistan has included LGBTQ+ Afghan representation. “We are erased even by those who call themselves progressives.”

While precise statistics are difficult to obtain due to criminalization and fear, advocacy groups estimate that thousands of LGBTQ+ individuals live in hiding in Afghanistan, and hundreds have fled since 2021. In Pakistan, estimates suggest over 500 documented cases of violence against transgender people annually, with Afghan refugees among the most vulnerable.

In Europe, LGBTQ+ Afghan refugees report higher levels of safety but continue to face trauma, social isolation, and intra-community hostility.

Mehrmah’s Message

Despite everything, Mehrmah refuses to be silent.

“For people like us, life under the Taliban is hell,” she says. “The world must never recognize them.”

Her story is not only about survival it is a testament to resilience in the face of systems that deny existence itself. For LGBTQ+ Afghans, freedom is not abstract. It is the difference between life and death.